Although I love to travel and have now lived in China for nearly three years, I have not actually travelled that much. I have also hardly taken any photographs here in Xi’an, where I have lived for most of that time. The first fact is not about to be rectified to any great extent, however, the second is. The link between these two points is my manual Olympus OM 10 camera, which I bought while travelling in Sri Lanka, on my way to India and not long before coming to China. Sadly, on my most recent travels I realized that a manual film camera is just no longer cost effective, with the additional price of film and developing it is just not practical these days.

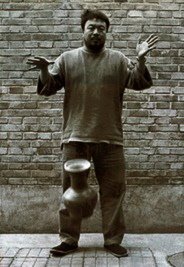

Therefore, while I am now in the process of buying a Digital SLR camera, I have been looking back on the last photographs my old OM10 took. These include my limited travels in China. I have decided to add a few of my favourites here, to one, acknowledge the enjoyment I had using my old camera, and two, to kick off the inclusion here, within these notes, of China based photographs, that I am sure my new camera will increasingly be taking, particularly here in Xi’an. Also, for three, these places are actually quite good places to visit. These pictures were taken in Xi’he, Gansu (1-9), Langmusi, Sichuan (10-11), Jiuzhaigou, Sichuan (12-14), Bamboo Forest, Sichuan (15-16), Lijiang, Yunnan (17-19), Lugu Hu, Sichuan/Yunnan border (20) and Litang, Western Sichuan (21-25).

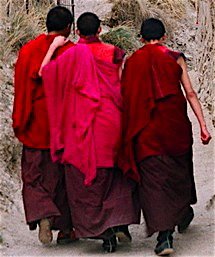

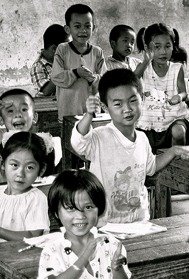

A number of these images include the Tibetan community, outside of Tibet, and when looking at them it reminded me of the few experiences I have had with Buddhism and meditation over the years. However, the mindfulness and attentiveness that I associated with those practices seems a million miles away from what one experiences in these communities. I have decided though to add as a backdrop to these images a brief introduction to meditation, as when I came across these methods sometime ago I found them particularly rewarding and looking at these images again, just reminded me of it. The passage is taken from a speech by Ajahn Sumedho at Amaravati Buddhist Centre in Britain:

'The word meditation is a much used word these days, covering a wide range of practices. In Buddhism it designates two kinds of meditation - one is called 'samatha', the other 'vipassana'. .JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

So for this kind of ability, you have to arouse effort from your mind, because the breath is not interesting, not romantic, not adventurous or scintillating - it is just as it is. .JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg) In Buddhist terms we use the word Dhamma, or Dharma, which means 'the way it is', 'the natural laws'. When we observe and 'practise the Dhamma', we open our mind to the way things are. In this way we are no longer blindly reacting to the sensory experience, but understanding it, and through that comprehension beginning to let go of it.

In Buddhist terms we use the word Dhamma, or Dharma, which means 'the way it is', 'the natural laws'. When we observe and 'practise the Dhamma', we open our mind to the way things are. In this way we are no longer blindly reacting to the sensory experience, but understanding it, and through that comprehension beginning to let go of it. .jpg) We begin to free ourselves from just being overwhelmed or blinded and deluded by the appearance of things. Now to be aware and awake is not a matter of becoming that way, but of being that way.

We begin to free ourselves from just being overwhelmed or blinded and deluded by the appearance of things. Now to be aware and awake is not a matter of becoming that way, but of being that way. .jpg) So we observe the way it is right now, rather than doing something now to become aware in the future. We observe the body as it is, sitting here. It all belongs to nature, doesn't it? The human body belongs to the earth, it needs to be sustained by the things that come out of the earth.

So we observe the way it is right now, rather than doing something now to become aware in the future. We observe the body as it is, sitting here. It all belongs to nature, doesn't it? The human body belongs to the earth, it needs to be sustained by the things that come out of the earth. .jpg) You cannot live on just air or try to import food from Mars and Venus. You have to eat the things that live and grow on this Earth. When the body dies, it goes back to the earth, it rots and decays and becomes one with the earth again.

You cannot live on just air or try to import food from Mars and Venus. You have to eat the things that live and grow on this Earth. When the body dies, it goes back to the earth, it rots and decays and becomes one with the earth again..jpg) It follows the laws of nature, of creation and destruction, of being born and then dying. Anything that is born doesn't stay permanently in one state, it grows up, gets old and then dies.

It follows the laws of nature, of creation and destruction, of being born and then dying. Anything that is born doesn't stay permanently in one state, it grows up, gets old and then dies. .jpg) All things in nature, even the universe itself, have their spans of existence, birth and death, beginning and ending. All that we perceive and can conceive of is change; it is impermanent. So it can never permanently satisfy you.

All things in nature, even the universe itself, have their spans of existence, birth and death, beginning and ending. All that we perceive and can conceive of is change; it is impermanent. So it can never permanently satisfy you..jpg) In Dhamma practice, we also observe this unsatisfactoriness of sensory experience. Now just note in your own life that when you expect to be satisfied from sensory objects or experiences you can only be temporarily satisfied, gratified maybe, momentarily happy - and then it changes.

In Dhamma practice, we also observe this unsatisfactoriness of sensory experience. Now just note in your own life that when you expect to be satisfied from sensory objects or experiences you can only be temporarily satisfied, gratified maybe, momentarily happy - and then it changes.

The article continues here.

Friday, 24 April 2009

Meditation and The Last Days of my Manual Camera

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment